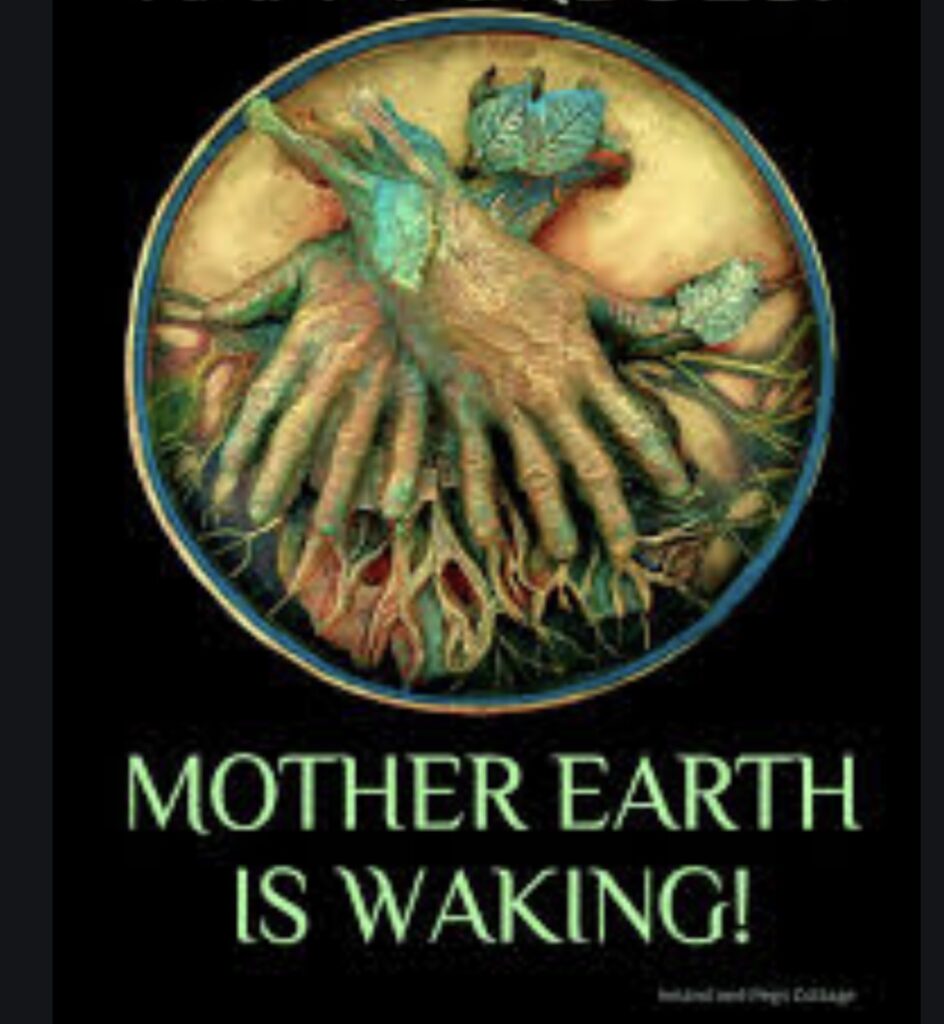

At the mid point between winter solstice & spring equinox Spring stirs

This Celtic festival honours the goddess Brigid, who represents the maiden, and heralds the beginning of the awakening of nature.

St Brigid and her magic cloak

St Brigid of Kildare or Brigid of Ireland (c. 451-525) is one of Ireland’s patron saints along with Saints Patrick and Colm Cille. Her feast day is 1 February or Imbolc, the traditional first day of spring in Ireland. She is believed to have been an Irish Christian nun, abbess, and founder of several convents.

Imbolc is a Gaelic traditional festival marking the beginning of spring. Most commonly it is held on 1 February, or about halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals—along with Beltane, Lughnasadh and Samhain. At Imbolc, Brigid’s crosses were made and a doll-like figure of Brigid, called a Brídeóg, would be paraded from house-to-house. Brigid was said to visit one’s home at Imbolc. To receive her blessings, people would make a bed for Brigid and leave her food and drink, while items of clothing would be left outside for her to bless. Brigid was also invoked to protect homes and livestock. Special feasts were had, holy wells were visited and it was also a time for divination.

In Irish mythology Brigid was the Celtic goddess of fire, poetry, unity, childbirth and healing. She was the daughter of Dagda a High King of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Sacred wells were always places of pilgrimage to the Celts. They would dip a clootie (piece of rag) in the well, wash their wound and then tie the clootie to a tree. Generally a Whitethorn or Ash tree, as an offering to the spirit of the well. It seems only natural that these traditions would be carried forward into modern times in the form of St Brigid.

In, If women rose rooted, I read, “That’ll put the jizz back in you,’ said old Brid, her eyes glinting, as she handed me a bowl of real water from the purest well in Gleann an Atha. A well kept sweet and neat by her people’s people, the precious legacy of her household, tucked away in a nook, a ditch around it for protection, a flagstone on its mouth. . . . But for a long time now there is a snake of pipe that leaks in from distant hills and in every kitchen, both sides of the glen, water spits from a tap; bitter water without spark that leaves a bad taste in the mouth and among my people the real well is being forgotten. ‘It’s hard to find a well these days,’ said old Brid, filling up my bowl again. ‘They’re hiding in rushes and juking in grass, all choked up and clatty with scum but for all the neglect they get their mettle is still true. Look for your own well, pet, for there’s a hard time coming. There will have to be a going back to sources.” from ‘The Well’ by Cathal Ó Searcaigh

Pegs Cottage